The toothless steersman positioned the rudder. A second sailor, balancing barefoot on an outrigger, coaxed an elderly engine into life. A third poled the boat away from the trash-strewn beach. In West Sulawesi, Indonesia, a ground-breaking mobile library was on its way.

In 2015, Alimuddin decided to combine his twin passions for books and boats by setting up a mobile library (Credit: Theodora Sutcliffe)

The Perahu Pustaka (Book Boat) is sorely needed. In a recent study of 61 nations for which data was available, Indonesia ranked second worst for literacy – only Botswana scored lower. More than 10% of the West Sulawesi's adult population cannot read, while in many villages, the only book available is a solitary copy of the Quran.

So in 2015, local news journalist Muhammad Ridwan Alimuddin decided to combine his twin passions for books and boats by setting up a mobile library on a baqgo, a small traditional sailboat. His aim? To bring fun, colourful children's books to remote fishermen's villages and tiny islands in the region where literacy is low and reading for pleasure virtually non-existent. He preaches the joy of reading.

Alimuddin's famous boat is called the Perahu Pustaka, or Book Boat (Credit: Theodora Sutcliffe)

“As soon as the boat was built, I sent an email to my boss resigning,” he said.

Not that the boat is the limit of Alimuddin's library ambitions. A physical library in his home village of Pambusuang on the West Sulawesi coast contains thousands of volumes, drawing students from local high schools and even university, as well as hordes of village children. He has a motorbike and rickshaw for transporting books overland, as well as an ATV, which he uses to reach isolated mountain villages, some only accessible by crossing rivers on a bamboo raft.

But it's the boat library that's closest to Alimuddin's heart. Despite never finishing university, he has written 10 books on maritime culture and helped sail a small traditional pakur craft from Sulawesi to Okinawa in Japan. His love of the sea can be seen in his maritime museum, a collection of model and antique boats, which shares space with his library. And he uses the boat journeys, which can mean up to 20 days at sea, to research and make YouTube documentaries on the fishing and seafaring life of his native Mandar people.

Children of remote communities now have access to books (Credit: Theodora Sutcliffe)

Since 2015, Alimuddin has criss-crossed South, Central and West Sulawesi, bringing boxes of books and comics from his 4,000-strong library to the children of remote communities as often as his budget permits. Sometimes his young son, who is home-schooled, comes with him.

As we closed in on the oyster-farming village of Mampie on the West Sulawesi coast, a gaggle of children emerged from the palms to watch the library boat pull in. Others stopped the hard, repetitive work of shucking oysters as Alimuddin, a volunteer from his home village and his crew of three unrolled plastic mats and covered them in books.

Alimuddin's boat provides books of all kinds and for all ages (Credit: Theodora Sutcliffe)

Excited children dived into the brightly coloured tomes; their mothers, some with babies, were more circumspect.

“We have low expectations,” Alimuddin said. “We want them to use the books – that's all.”

With more than 17,000 islands scattered across the Indian and Pacific oceans – some virtually in the Philippines, others close to Australia or butting up against Singapore – education in Indonesia is a constant struggle. Although there are plentiful primary schools, even in small islands and remote villages, facilities are often decayed. Resources and teachers are harder to come by; it's not unusual for teachers, suffocated by the social constraints of island life, to fail to show up for work.

“We have low expectations... we want them to use the books – that's all” (Credit: Theodora Sutcliffe)

After three hours in Mampie watching the children devour the books, we packed up and set sail along the coast for the nearby island of Battoa, home to around 2,000 people scattered between several villages. The book boat pulled into the mangroves and moored at a shell midden; Alimuddin scrambled ashore to look for children.

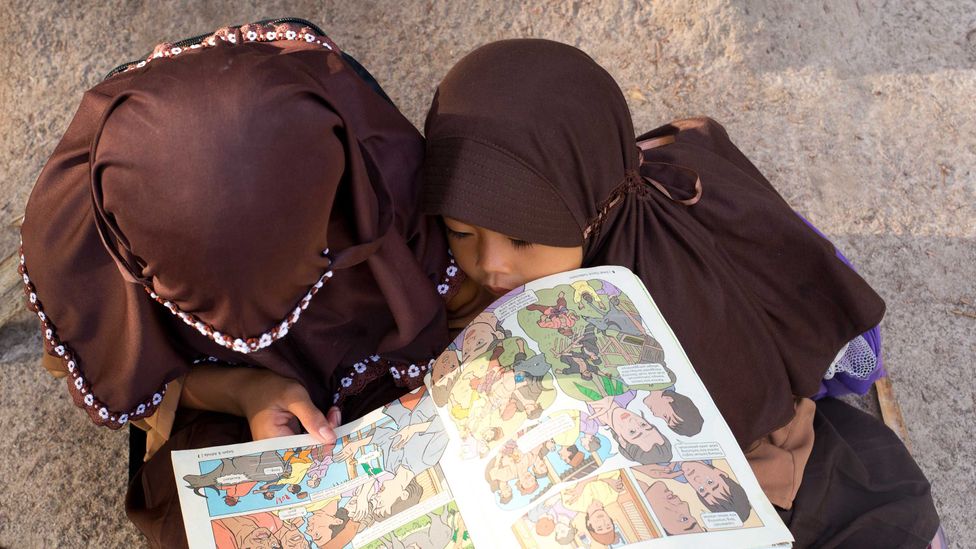

Under the trees, the books came out: comics, cartoons, books on Ancient Egyptians, dinosaurs, science, dolphins, princesses, Indonesian heroes and tales from the Quran. Within seconds, 20-odd children had appeared from the hinterlands. The comics went fast, as did the brightly coloured picture books written half in Indonesian and half in broken English.

The Book Boat contains almost 4,000 books onboard (Credit: Theodora Sutcliffe)

Alimuddin runs his library entirely on donations – some from businesses, some from friends, others from people who've seen his activities on social media. A sponsor had recently donated some jigsaw puzzles, which he used as gifts to motivate a discussion about books.

We anchored for the night on a striking white sand islet not far from Battoa, populated only by a gaggle of stray cats, ate a simple dinner and caught a spectacular sunset. Close to the equator, the night was warm enough to sleep on deck.

Long before 7 am, we were on our way to the village school on the island of Tangnga, a few kilometres east of Battoa, where tiny children in pristine uniforms were already awaiting the arrival of their teachers from the mainland.

The arrival of Alimuddin's boat is often a source of excitement for these children (Credit: Theodora Sutcliffe)

“We're just 3km from the district capital [of Polewali],” Alimuddin said, gesturing at the ramshackle buildings with their broken furniture, bereft of books or artwork. “And you see?”

The kids fell on the books and clustered in small groups under the bamboos. The air filled with the steady hum of voices reciting out loud. Some read to younger siblings, others to themselves.

“When you see a child smile and open a book, all your problems disappear,” Alimuddin said with a smile of his own.

“When you see a child smile and open a book, all your problems disappear” (Credit: Theodora Sutcliffe)

If you liked this story, sign up for the weekly bbc.com features newsletter, called “If You Only Read 6 Things This Week”. A handpicked selection of stories from BBC Future, Earth, Culture, Capital, Travel and Autos, delivered to your inbox every Friday.