When the titular Saltburn first appears in Emerald Fennell's new film, the camera lingers on the stately home. It is vast: a symmetrical hulk of limestone topped off by pediments, towers, castellated parapets, and cupolas; its impenetrable grey flanks shrouded by trees and wrought-iron gates. Oliver Quick (Barry Keoghan) stands there, taking it in. In a button-up plaid shirt with an unwieldly suitcase, he is an interloper from another world – one whose first social faux pas is to make his way slowly through the various gates and arrive at the imposing front door on foot, rather than wait to be picked up from the train station by a servant.

Warning: this article contains offensive language

More like this:

– Britain's most scandalous family

– The school that rules Britain

– The colonial history of the British countryside

At first glance, Saltburn is classic clash-of-the-classes fare: a tale of social strata, moral vacuity and the seductions of wealth, with a poor boy ushered into his rich friend's kingdom. The rich friend, in this case, is Felix Catton (Jacob Elordi), a handsome Oxford undergraduate whose life is charmed by the confidence and social grease that comes from being in possession, as a fellow student puts it, of a hereditary title and a "fuck-off castle". The year is 2006, and the magnanimous Felix has invited Oliver – who possesses neither money, popularity, nor a stable home life – to stay at Saltburn for a fateful summer.

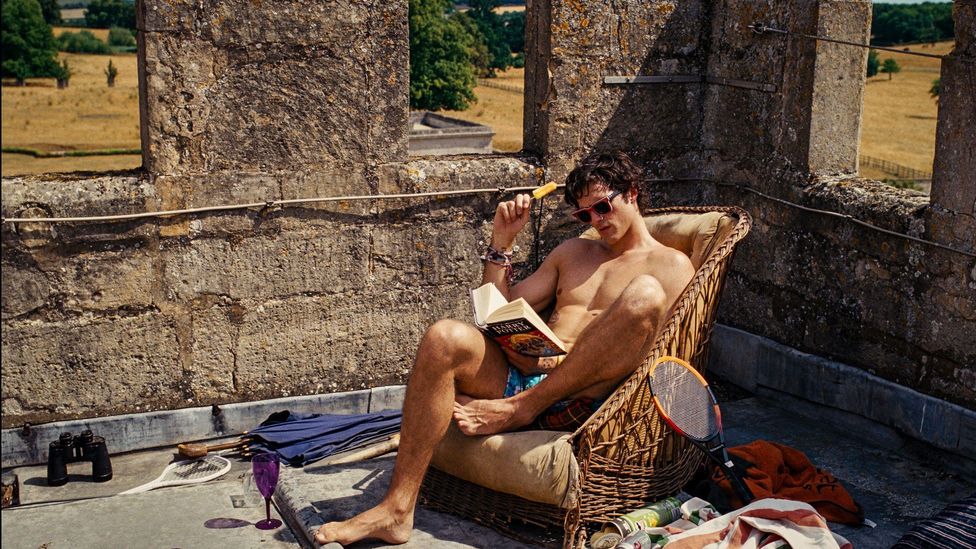

Saltburn is centred around a summer at a stately home, where eccentricity and debauchery thrive (Credit: Alamy)

Oliver immediately gets a guided tour, Felix wheeling through libraries and endless colour-coded rooms, up and down staircases and along echoing halls where various "dead relly[s]" stare down from the walls. In less of a nod than a jabbed finger to the film's own forebears, Felix drops in a mention of Evelyn Waugh being reputedly obsessed with the place. All of this is a calculated set-up, Saltburn intended to seduce the viewer with grandeur as much as it might hope to imply ominous things lurking under the surface.

The stately home has long exerted a compelling hold – part-charmed, part-tragic – over the British imagination. It's a hold that Fennell's film both wants to subvert and unabashedly tap into. From the works of Jane Austen and novels including Waugh's Brideshead Revisited (1945), D H Lawrence's Lady Chatterley's Lover (1928), Nancy Mitford's The Pursuit of Love (1945), Daphne du Maurier's Rebecca (1938), and Ian McEwan's Atonement (2001) to costume dramas such as Downton Abbey and Bridgerton, there's a particular narrative allure to houses full of secrets and staff quarters. The big country house lends itself especially well to romances, whodunnits and gothic drama, a combination of beauty, scale and isolation, as well as bizarre inhabitants, providing apt settings for both the lightest and darkest of themes.

Like those many works before it, Saltburn plays with the idea that these enormous bastions of privilege and power are unique breeding grounds for strangeness – and, crucially, magnets for it too. Cut off both physically and financially, eccentricity and emotional indifference can flourish behind the gates. However, as with those other works, its characters pale by comparison to the generations of real-life aristos who have populated the country's 600 or so stately homes over the centuries.

The most eccentric owners

Take William John Cavendish Scott Bentinck, the fifth Duke of Portland, a 19th-Century recluse who turned his home Welbeck Abbey in Nottinghamshire into a warren: painting most of the rooms pink and constructing an elaborate system of tunnels beneath the property that stretched to 15 miles (24km), connecting his house to the nearest train station. Or Sir Tatton Sykes, a baronet who loathed flowers with such a passion that on moving into Sledmere House in Yorkshire in 1863, he decreed that every single one be destroyed – including those in the gardens of the village that also sat on the estate. Or Gerald Hugh Tyrwhitt-Wilson, the 14th Baron of Berners, who dyed the feathers of his pigeons in bright colours, took afternoon tea with a pet giraffe, and drove around the estate of Faringdon House in his Rolls-Royce wearing a pig's mask to scare the locals.

The 2008 film of Evelyn Waugh's Brideshead Revisited, which for many is the ultimate stately-home drama (Credit: Alamy)

And then there's Henry Cyril Paget, the fifth Marquess of Anglesey, who hired a professional theatre company and put on hugely ambitious performances at his home in Plas Newydd as well as touring across Europe – with himself as the star attraction. With a taste for jewels and other extravagances, he also managed to burn through his £535,000 (about £60m by today's standards) inherited estate in just five years, bankrupting himself and dying from tuberculosis at the age of 29.

In the abstract, such stories are often intriguing, if not downright entertaining. Who doesn’t want to read about dinner parties thrown for formally dressed dogs à la Francis Egerton, Eighth Earl of Bridgewater? Or learn about the brief 18th-Century craze for ornamental hermits employed to live out their silent, lonesome days in specially built garden follies? But even in relaying these juicy, ridiculous facts, there is an immediate sense of something gross, of singular tastes indulged by deep pockets, of eccentricity insulated by power. It's easier to be a hoarder in a house with 30 rooms, after all, or turn a whim into an edict when you own everyone else's homes.

We're in an era where we're much more keenly aware of the exploitation and suffering that facilitated the creation of these grand country houses … it's harder to sink into the escapism when you can see the blood beneath the bricks

In Saltburn, Fennell attempts to combine the gross and the visually spectacular. It doesn’t quite land, let down by the film’s tonal unevenness. Her dialogue glitters, and in the hands of a stellar cast including Rosamund Pike, Richard E Grant and Carey Mulligan, it's often hilarious. But Fennell wants to shoot for the black heart of a story, to reveal the depravity beneath the glamour. This would be effective if her characters didn't lack the depth and sometimes even the motivation to make their actions plausible. It's as though one can see the bullet-pointed themes laid out, the arrows drawn towards the predictably Talented Mr Ripley-esque conclusion. If the film's final scene – no spoilers, but one could say that it's another guided house tour of sorts – is its most sublime, it also serves as a cinematically smart alec moment to work back from, constructing a leaky plot that will allow it to take place.

The darkness behind closed doors

The larger problem is that the stately home drama feels like an increasingly stale genre, even if you try to twist it. Fennell's script repeatedly makes the argument that the rich are callous, though her humour works counter to that here too – sometimes they're so funny that even their outrageous statements become oddly endearing. But such observations feel so obvious as to be a given, especially in an era where we're much more keenly aware of the exploitation and suffering that facilitated the creation of many of these grand country houses, funded by fortunes made from slave-trading, sugar plantation ownership, colonial administration and so on. It's harder to sink into the escapism when you can see the blood beneath the bricks.

Gerald Hugh Tyrwhitt-Wilson, the 14th Baron of Berners, is among the aristocratic estate-owners remembered for their bizarre whims (Credit: Getty Images)

In the here and now, the UK's stark wealth inequality also forces a question of focus. Why is this thin sliver of society one we continue to find so compelling? Many of those novels written after World War One, including Waugh's, traded on the idea of an aristocracy that was slowly fading away. It's a cliché we still recognise today: moth-eaten cardigans, ruddy noses, muddy boots, unspoken feelings, animals everywhere (adored if pets, shot if prey), freezing houses that leave their owners asset-rich but too cash-poor to heat them.

Today, many stately home owners will say that they have been forced to open the doors to their homes to keep them going, whether that means giving guided tours or turning them into wedding venues and film locations. (Saltburn was filmed at Drayton House in Northamptonshire, although apparently the crew are not allowed to publicly acknowledge the location as it is still a private family home.)

True as this may be, it also obscures the fact that a third of the land in England and Wales remains in the hands of the aristocracy, who have proved themselves to be remarkably resilient. The worth of a hereditary title has nearly doubled since the 2007 financial crisis, now standing at more than £16m.

As the i reported in 2019, aristocratic fortunes have been on an explosive upward incline since the 1980s, the post-Thatcher world of financial deregulation bringing new opportunities for investing and asset management. The stately home as it still exists not just in the British imagination but the general cultural ether is a useful smokescreen, perhaps allowing the aristocracy to escape deeper scrutiny, carrying on behind closed doors.

If you liked this story, sign up for The Essential List newsletter – a handpicked selection of features, videos and can't-miss news delivered to your inbox every Friday.

If you would like to comment on this story or anything else you have seen on BBC Culture, head over to our Facebook page or message us on Twitter.