"I can't smell the water," Chris Brunet says as he sits on the front porch of his new home in Gray, Louisiana. "I can't smell it, I can't see it, I can't sense it. And I miss it."

Brunet, a member of the Biloxi-Chitimacha-Choctaw Tribe, lived most his life on Isle de Jean Charles, a small strip of land about 40 miles (64km) away in Terrebonne Parish, Louisiana, which has lost 98% of its land to coastal erosion.

Alongside his neighbours, Brunet made the decision to leave his home, and all he knew, to move to higher ground in 2023, in a mammoth multimillion dollar project to relocate the tribe to escape rising sea levels. The tribe had already run once – from white settlers during the colonisation of America – and fled to the island, which was an isolated refuge until 1953, when a road was built that connected it to the mainland.

Now, they felt they were being forced to flee again, and wanted to change the narrative. "We are not climate refugees," Brunet insists. "We are climate pioneers."

It is an important distinction, particularly as the forced migration of Native Americans has made tribes more vulnerable to climate change impacts.

Call out Box: Sign up to Future Earth

Sign up to the Future Earth newsletter to get essential climate news and hopeful developments in your inbox every Tuesday from Carl Nasman. This email is currently available to non-UK readers. In the UK? Sign up for newsletters here.

The tribe's new neighbourhood has been named "the New Isle", a homage to Isle de Jean Charles. "It's still our island. It will always be our island," says Brunet, who only agreed to move if he could keep his old house too. He returns when he can. But it's not the same.

A losing battle

Louisiana, which is bisected by the 2,340 mile-long (3,766km) formidable Mississippi River, is a state especially vulnerable to the effects of climate change. Many of its populated areas, including New Orleans, lie below sea level. People regularly lose cars to flooding triggered by heavy rain, while others are unable to evacuate from hurricanes because they lack the means. For the Isle de Jean Charles tribe, coastal erosion and rising seas were the primary threat.

Chris Brunet sits outside his new house in Gray, Louisiana, after coastal erosion forced him to leave his old home. 'We are climate pioneers,' he insists (Credit: Lucy Sherriff)

Brunet grew up dealing with high winds and tidal floods. He remembers as a child the water coming right underneath his family home's floorboards and submerging the one road that led on and off the island. "For us, that was playtime. We'd get in the pirogue (a Cajun canoe-style boat), and we'd play until the tide would go out. Sometimes it'd be two days later," he says.

The tribe had talked about leaving. "But that's all it was. It was like OK 'let's drink coffee and eat bread and talk about the economy or relocating.' It didn't become real until about 1998."

In 1998, Louisiana was struck by category four Hurricane Georges, and major tropical storms hit every year after that until Hurricane Katrina slammed the state's coast in 2005, causing almost 2,000 fatalities, $108bn (£85bn) in damage in the region, and leaving nearly 900,000 Louisianans without power. The islanders rebuilt, but in 2021, along came Hurricane Ida, devastating their homes once again. Many of the houses are still in pieces; footbridges lead to rubble, and naked stilts protrude from the ground the building which once sat atop them ripped clean off.

We did not want to be climate refugees. We are climate pioneers – Chris Brunet

It wasn't the hurricanes themselves that bothered Brunet, however, it was the erosion that they – alongside the oil and natural gas drilling – caused, he says.

"We could deal with hurricanes," says Brunet. "We've always had hurricanes, I was raised with those challenges. But our island was disappearing."

You might also like:

- The UK 'climate refugees' who won't leave

- The floating homes built for floods

- Why US ranchers are becoming beaver believers

The coastal areas of Louisiana were created by sediment deposits about 5,000 years ago. The sediments gradually compact, causing the land to sink one inch (2.5cm) every three years. Historically, when the river would overflow its banks, new sediment would be deposited onto the land, keeping pace with the rising sea level and the sinking river delta. But humans have thwarted the natural process of the river. That, coupled with sea level rising at an increasing rate, means Louisiana has been losing between 25 and 35 sq miles (65 and 91 sq km) of land per year in recent decades – an area larger than Manhattan.

The Gulf Coast, the region where Louisiana sits, is now undergoing unprecedented historical erosion, with south Louisiana, where Isle de Jean Charles lies, experiencing the greatest impact: a 25% loss of its wetlands. Research has shown that decades of dredging of canals by the oil and gas industry has contributed to the loss of wetlands and altered the hydrology of the area. The energy companies that operated there insist that they have acted lawfully.

The waterways around Isle de Jean Charles used to be narrow and intricate; now they're much wider, due to coastal erosion (Credit: Lucy Sherriff)

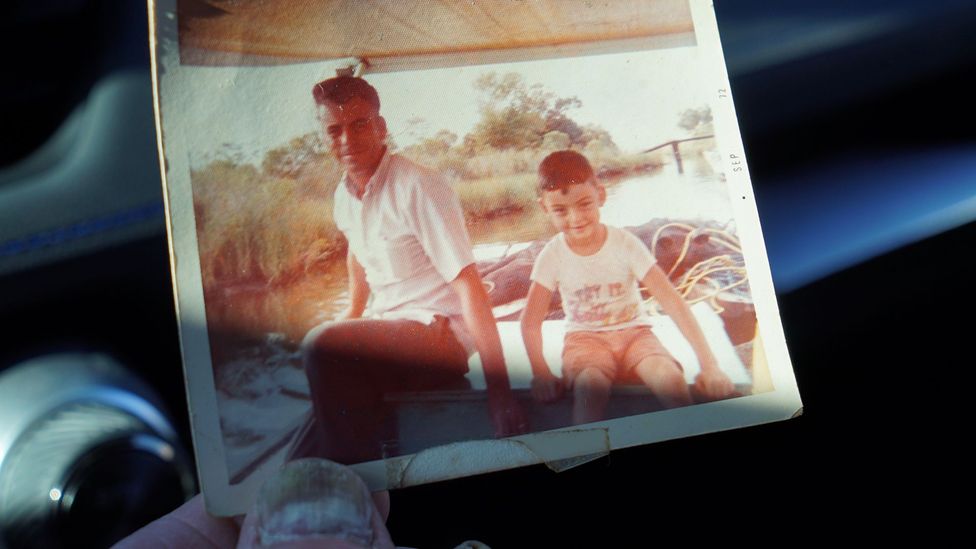

It was erosion that made Brunet's mind up. His father was a commercial fisherman, out on the marshes every day. "As the years went by, there was less land and more water. My dad would say a category one storm wouldn't bring flooding to the island. With so many miles of marsh, they would absorb the surge coming in and it wouldn't make it to the island. Now that's changed," he says.

Where there were intricate pockets of bays and bayous which Brunet's father would deftly navigate in his pirogue, now there were just vast expanses of water, with no marsh. "The landscape was sacrificed by the oil and gas industry," Brunet says. "They'd come in and tear up the land to bring these rigs in. They changed the landscape."

Brunet and his community knew they were fighting a losing battle. The nail in the coffin came when the US Army Corps of Engineers decided to leave Isle de Jean Charles out of a new levee system – essentially a flood wall – it installed in 2022 to protect the rest of Terrebonne Parish. "We were supposed to be included," Brunet says, "but because of the cost they decided not to save it. The property value is not all that great". Brunet felt the Army Corps considered his home "not worth saving".

The Army Corps deemed the best course of action was for the residents to move. "The recommended non-structural approach was relocation," a spokesperson tells BBC Future Planet. "When we looked at the inclusion of Isle de Jean Charles within a levee alignment, the cost to extend and maintain the alignment around the community would have been much greater than the damages that would have been prevented."

By that point, Brunet – who had agonised over whether to leave – resigned himself to moving. "I knew I was up against something that I couldn't stop on my own. I just didn't think it would happen in my lifetime." The rest of the community felt similarly, and joined Brunet with heavy hearts. Three families chose to stay behind, and still live on Isle de Jean Charles.

Chris Brunet's father would go out fishing everyday when the bayou's waterways were still narrow and intricate. (Credit: Lucy Sherriff)

Mass relocation is stressful no matter what the circumstance, says Melissa Walls, co-director of the Center for Indigenous Health at John Hopkins Bloomberg School, Minneapolis. "For indigenous peoples, policies and practices related to historical trauma and settler colonisation have included forced and coercive relocation policies," says Walls, who is of Couchiching First Nation and Bois Forte Band of Ojibwe descent. "The effects of these traumatic experiences have been shown to ripple out to affect subsequent generations, negatively impacting family connections, mental health, and overall wellbeing.

"Given all this, additional displacement or relocation experiences for Indigenous Peoples represent another layer of accumulating trauma – potential triggers, if you will."

Walls, whose recent study examined the influence of historical trauma on Indigenous families in the US, highlights the efforts of indigenous groups to revitalise their culture and connection to place, and how relocation is a step back in this process.

A new island

In 2016, the community teamed up with the State of Louisiana to enter a competition run by United States Department of Housing and Urban Development. Entrants needed to prove why they should be the recipient of a $48.3m (£38m) grant. The National Disaster Resilience Competition was the first of its kind, aimed to help communities respond to climate change. Almost $1bn (£784m) in funds were awarded to 13 states and communities. The department received proposals which amounted to $7bn (£5.5bn).

The Isle de Jean Charles community ticked all the boxes: they're a tribe, they were willing to move – and soon – and they were watching their homes be consumed by water before their very eyes.

When the opportunity for the funding came up, community leader Chief Father Albert Naquin pushed his tribe to apply. It had not been easy to get to this point. Indigenous communities have a sacred connection to their environment, believing they are stewards of the land – or water –they live on. "We are culturally tied to the land," says Brunet.

With the community's buy-in, and the help of the state, they applied. And won.

Finding a suitable place to move to was going to be a challenge. Anywhere that had flooded before was out of the question. "We weren't going to go through the trauma of moving if we had to face the threat of flooding again," says Brunet. In the end, there were only three suitable sites that were offered to the tribe. The state consulted with them to determine which would be bought.

A small shack used to serve as the island’s social club. It was severely damaged by Hurricane Ida, and locals didn’t have the financial means to repair it (Credit: Lucy Sherriff)

"One of the things we learned was how absolutely critical it is to talk to individuals about their priorities, as opposed to trying to get a general feel from a leadership structure," says Pat Forbes, executive director of the state's office of community development. "It's impossible to get a good clear understanding of people's thoughts about their future without talking directly with them. It was extremely enlightening."

Consultations and land evaluations began in December 2016. The state held one-to-one meetings with tribe members at their homes, to enable individuals to speak freely. Priorities included staying together to maintain their cultural identity, privacy, seclusion, access to water, and finding land that had as little risk of flooding as possible. Residents were able to visit the potential sites, and chose a consulting team that would develop a master plan for the new site. A steering committee was appointed to act as liaisons between the state and the community, and an independent academic advisory board offered advice and insights into the environment and resettlement process.

In December 2018, the site, 515 acres of rural land in Terrebonne Parish, was purchased for $11.7m (£9.2m), with a plan to build 120 homes. Walking trails, a community centre, commercial and retail spaces are also included in the plans. Residents were offered a choice of house. "You could choose a single storey, two storey," Brunet says, "the colour scheme, the cabinet work, the flooring".

There was a three-tier approach to the voluntary resettlement. Residents whose primary residence was on the island were given priority, as well as residents who had been displaced by 2012's Hurricane Isaac, a deadly tropical cyclone which killed 34 people. They could apply to receive a new home of their choosing built on the New Isle. In the second tier were residents who did not want to move to the new site, but fit the criteria of the first tier. They could apply for funding towards buying an existing home in Louisiana, as long as it was located outside the 100 year floodplain – the high risk region defined by the Federal Emergency Management Agency that has a 1% chance of a massive flood event occurring in any given year. The final tier included residents who were displaced from the island prior to Hurricane Isaac, or who were displaced post-Isaac but already own an off-island home.

Eligible families that opted to resettle signed a forgivable mortgage agreement; one fifth of the mortgage would be forgiven each year for five years, during which time no payments are required. After five years of simply residing at the property, the resident then owns it in full.

A grieving process

For the tribe, it has been – and still is – a process of collective grieving. They are mourning their connection to the land, which must now be upheld internally, and their sense of place. It's a grief that is only compounded by the historical and intergenerational trauma of having been displaced once before from their ancestral lands.

"I've had to grieve," says Brunet. "Not a death of the island, the island is still there. But I've had to grieve over moving. Because I had to leave a place, the only place I ever knew as home. It's grieving that sense of belonging."

The houses on New Isle are set back from the main road, down a smooth curving road – a far cry from the bumpy often flooded path Brunet would take to reach his former house. But instead of looking out across the web of marshy bayous, the salty inlets ruffled by a warm breeze, Brunet stares at the cookie cutter house opposite, trying to ignore the sound of rushing traffic from the nearby road and the churn of heavy machinery from the Chevron oil rig maintenance facility next door.

Thirty-four families have already moved from Isle de Jean Charles to The New Isle Community, 40 miles (64km) away in Terrebonne Parish, Louisiana (Credit: Lucy Sherriff)

Since August 2022, 34 families have moved to the New Isle. Some have already moved elsewhere in the state, and they have the option of joining the community. Three additional homes, as well as a community centre and a food market, are under construction, bringing the total number of families to 37. Initially, 41 families expressed interested in the relocation, but one resident passed away and three other families decided not to participate. There will be a further 27 homes built in the neighbourhood, which will be available for residents who had already left the island prior to the relocation, although the construction date is still pending.

Carbon count

The emissions from travel it took to report this story were 43kg CO2. The digital emissions from this story are an estimated 1.2g to 3.6g CO2 per page view. Find out more about how we calculated this figure here.

These kinds of resettlements are going to be more necessary as the impacts of climate change become increasingly severe. In 2022, the Biden administration announced three tribes – in Alaska and Washington – would receive $75m (£62m) divided equally between them to help fund a relocation. Between 2000 and 2020, more than 3.2 million people in the US moved out of "climate abandonment areas" – regions where population loss can be directly attributed to climate change related flood risk.

"Querying how we imagine and manage retreat is becoming increasingly urgent in the United States," Lizzie Yarina, a PhD candidate at MIT's department of urban planning, says in a 2020 study she co-authored. The paper analysed forms of managed retreat from environmental risks, such as sea level rise, and highlighted a lack of framework for these kinds of relocations. "One of the most pressing questions to ask in these kinds of situations is 'what does it mean to ask a community, with deep ties to their people and place, to relocate?'," Yarina says.

A choice

Choosing to move, as opposed to being forced to move, can have a huge impact on communities of colour and vulnerable groups, according to one study. "Compared to voluntary relocation, effects of compulsory relocation have been reported as significantly more negative in terms of subsequent social support disruption and psychological distress," the paper, which analysed the psychological and physical impact of relocation on Native American tribes, found. Additional effects of relocation included increased morbidity and mortality rates and cultural identity crises.

What does it mean to ask a community, with deep ties to their people and place, to relocate? – Lizzie Yarina

"This was not a forced resettlement," says Brunet. "This was all done on a voluntary basis. But I do feel forced. By climate change.

"We did not leave the place because we wanted to. We left because we felt we had no choice. We left because of coastal erosion."

The tribe felt very strongly that they did not want to be defined by the "climate refugee" label. Brunet noted that numerous media reports about the community had latched onto the phrase – something they deeply rejected. "And so we came up with another word for ourselves. We are climate pioneers."

Even though moving the residents of Isle de Jean Charles may have been a bittersweet success, Forbes cautions against looking to the resettlement as a viable solution for the rest of the country.

"While I've had the opportunity to take this project on to get this community to move, I would never hold it up necessarily as a model," says Forbes. "The scale is just so small compared to what we'll likely be facing in the future."

Brunet contemplates whether he is happy in this new place. He is not unhappy. But he'll continue to visit his home until either he dies, or the water engulfs it – whichever comes first. "It will always be home," he says. "It will always be where I belong."

--

If you liked this story, sign up for The Essential List newsletter – a handpicked selection of features, videos and can't-miss news delivered to your inbox every Friday.

Join one million Future fans by liking us on Facebook, or follow us on Twitter or Instagram.