The first time Sarah Corbett picked up a cross-stitch she was on a train to Glasgow, Scotland. Her hands were shaking and her breath was shallow. As she worked out how to do cross-stitch, she became increasingly aware of how stressed she was. The cross-stitch, which requires careful attention and slow, repetitive movements, made her realise she was feeling completely burnt out.

It was 2008 and Corbett, a lifelong activist, had spent her career so far working for charities such as Christian Aid and Oxfam on their campaigns.

In her spare time, she also attended activist groups campaigning for social and environmental causes, but she didn't feel like she fitted in with some of those groups. "I didn't like the abuse they were doing, or using activism as an excuse to be unkind and scream at people and do illegal things," she says.

As an introvert who dislikes confrontation, Corbett's activism had been taking a toll on her mental health. As she worked on her cross-stitch on the train and reflected on how she was feeling, the passengers next to her asked what she was doing.

Corbett was stitching a picture of a bear, and saw this as a missed opportunity. "I thought, if only I was stitching a quote by Gandhi, we could talk about inequality," she laughs. "Because my obsession is activism and social change, not craft."

She realised crafts could be a useful tool for starting conversations. This was her starting point for "gentle protest", a form of activism built on a slow, thoughtful approach rooted in empathy and contemplation.

Sarah Corbett thought there was another form of activism that could be effective besides conventional confrontation (Credit: Craftivist Collective)

Not long after her train journey, Corbett began researching craft and activism and soon came across the work of Betsy Greer, a knitter and anti-sweatshop activist, who had coined the term "craftivism" in 2003. Since then, craftivism has been taken in different directions by grassroots groups around the world, from straightforward awareness-raising, to punk-inspired "yarn bombing" public spaces by covering trees, lampposts and postboxes with knitted "graffiti".

Corbett became interested in the nonconfrontational, quiet, reflective nature of craft and began developing the idea of "gentle protest". Her approach focuses on a slow, contemplative kind of activism. "Use the slow, stitch-by-stitch nature of craft to help you consider the complexities of injustices. It will lead to a deeper understanding of them and their solutions," reads one point of her "craftivist manifesto".

Today, the walls of Corbett's flat in south London are lined with drawers, cupboards and suitcases of craft materials, examples of small gifts people have made embroidered with environmental slogans, and other social justice causes, such as LGBTQ rights and anti-racism. In one drawer, a small white cotton cloud reads "I dream of a healthy planet". A box of labels to sew into clothes contains messages such as "Good intentions are just the start".

The drawers and cupboards of Corbett's flat are filled with painstakingly crafted objects (Credit: Martha Henriques)

Corbett's approach is a world away from the noisy world of placards, marches and civil disobedience that prominent groups, such as Extinction Rebellion and Just Stop Oil, make headlines for.

"I think that's what makes it so powerful," says Lynn Sanders-Bustle, associate professor of art education at the University of Georgia, who has researched craftivism and the experiences of its participants. She believes the potential of craftivism comes down to three main elements.

First, Sanders-Bustle says the reflective nature of craftivism can lead to new perspectives. "In some of the sessions that [Corbett] implements, they gather this collective of people, and intentionally they pose questions that are related to the topic. So in other words, it's not enough to go out and protest climate. You're going to move the needle on your own learning and your own understanding of the issues," she says.

Second, there's the fact that these activities, though they can be solitary, are often done in a group. "You're bringing people together, and you are working on a project together," says Sanders-Bustle. "We are hearing more and more about the need for community and the need for social interaction. And there's almost a meditative component to it, right? You're sitting there, you're working, you're gluing, you're knitting, you're yarning. That's where there's potential for people to relax, reflect, be open to others' ideas," she says.

And the final piece, says Sanders, "is that it's a creative project. And in my mind, it's through a creative project that new solutions are generated, whether it's climate or anything else. It's through imagination," she says.

It might seem counterintuitive that a form of protest that can be solitary, reflective and thoughtful has reached so many. For a quiet form of protest, its ripples are spreading far and wide.

The "gentle protest" movement aims to use empathy and thoughtfulness to send a message (Credit: Craftivist Collective)

There are no formal estimates of how many people have taken part in craftivism, and much of its impact can be inherently hard to track. But some craftivist groups have certainly expanded rapidly in recent years. The Craftivist Collective, founded by Corbett, has held events in New Zealand, France, Spain, the US, Canada, and the UK among others. Corbett says leaders such as Christiana Figueres, the former lead climate diplomat for the UN and an architect of the Paris Agreement, have worn one of Corbett's creations.

Beyond climate, craftivist movements such as the Pussyhat Project, a knitting circle set up to protest against Donald Trump's presidency at the Washington Women's March in 2017, have become iconic.

The movement can be seen as an evolution of the "participatory turn" in art in the 1990s, says Sanders-Bustle. "Instead of wanting to create these objects that would hang in museums, artists wanted to create art that was devoted to social change," she says. "Socially engaged art, craftivism and this gentle kind of protest are connected."

Sanders credits the New Mexico artist Cannupa Hanska Luger as someone who bridges this form of art and craftivism. Luger, who was born on the Standing Rock Reservation in North Dakota, published guidelines on how to make a "mirror shield" for use by protestors at Dakota Access Pipeline protests in the Standing Rock Sioux Tribe Reservation in 2016. Since then, the shields have been used at multiple protests around the world.

"Socially engaged art, craftivism and this gentle kind of protest are connected," says Lynn Sanders-Bustle (Credit: Craftivist Collective)

The growth of craftivism is just one facet of how contemporary climate action is evolving. Climate action comes in many forms, such as donating money to climate-focused organisations, contacting politicians to urge them to address climate change, volunteering for a climate-focused cause, or attending a climate protest. These actions are not a niche activity for the highly politically engaged – in 2021, 24% of US adults had done at least one of these in the preceding year.

But climate action is showing signs of subsiding in the US, with this figure falling to 21% in 2023. The polarisation of who takes part, however, has remained the same – people most engaged in climate action tend to be young and left-leaning. And only 28% of US adults believe that climate protests, such as attending rallies or marches, makes a positive difference for the climate (21% believe it's counter-productive). Of Republicans, 78% viewed climate activists with suspicion.

Feeding into this suspicion is what's known as the "activist's dilemma" – that extreme protest actions raise awareness while at the same time eroding support for a social movement. That said, there's also evidence that a small minority or extreme flank of a movement can increase support for moderate factions.

You might also like:

- The science of climate protest – does it work?

- What the '3.5% rule' means for peaceful protest

- How the biggest environment movement in history was born

"Especially in the US, politics is very divided, and it's very this or that," says Sanders-Bustle. "And so how do we ever get to the subtleties and nuances, unless we open a space where that can happen? I think that's what craftivism does."

Creating handmade items has a long and multifaceted history in the protest movement (Credit: Craftivist Collective)

Over in the UK, Lorna Rees says that craftivism has done just that for her family. Rees lives near Christchurch, Dorset, on the UK's south coast. When she sat down with her family on the quayside at Christchurch for a crafting project organised by Corbett in 2021, it was the first time Rees' mother, her sons and nephews had all taken part in climate action together.

"We vote quite differently, but we could all be on board with this issue," says Rees. "We could all see there's something happening here that's beyond party politics."

Rees, who is on the political left, had taken part in many conventional protests before, and runs workshops on making humorous placards. Her mother had never been involved in activism before, but had concerns about protecting nature and the environment in her local area. Sitting and crafting allowed the family to discuss the climate crisis and share their concerns and support.

"We're on the coast and we're seeing a lot of flooding, and we're losing a lot of our coastline," says Rees. "The things that are happening in our planet and in the weather systems is having a really big local impact on us."

The lack of confrontation helped them have an open conversation, says Rees. "It's about being very present and doing it together. We weren't doing something that felt aggressive in any way."

Local passers-by took an interest in their crafting and asked them what they were doing. They explained they were crafting yellow canaries out of felt, a symbol of the "canary in the coalmine", acting as a warning system on the urgency of the climate crisis.

"It was non-confrontational," says Rees. "It was a very lovely, calming way of making a statement – of saying we're really worried about the climate crisis, but without having conflict. I think it brought our family together."

Once their canaries were crafted, Rees' family sent them to their local councillors with a message encouraging them to take climate change seriously.

The Pussyhat Project became an iconic image at the Washington Women's March in 2017 (Credit: Getty Images)

Larraine Larri agrees that the intergenerational appeal of craftivism is one of its strengths. Larri is a member of the Australian craftivist group Knitting Nannas, and carried out a PhD research project on the group before becoming a member.

Larri's background is in social sciences, evaluating school environment educational programmes to see how effective they are. Her work in the 2000s to the mid-2010s left her confident that school environmental educational programmes were working. "The kids were getting it, but I was worried that adults were not getting it. I was able to think about what is it that's going to change adults' views to actually take climate change seriously?"

Larri began researching whether craftivism could fill this space in adult education. She studied the Knitting Nannas, based in Lismore in New South Wales, Australia. The group formed in response to a mining company's interest in exploiting local coal seam gas deposits through hydraulic fracturing (fracking). The group hosts knit-ins in public spaces, often outside the offices of political representatives.

"I asked one of the first Knitting Nannas, what do people ask you when you are out knitting?" says Larri, who explains that they're usually asked what they're making. "We say, a statement," the woman told her. "In educational terms, that's a challenge to think differently," says Larri.

The Knitting Nannas grew from its original group (or "loop") to more than 40 across Australia in just a few years.

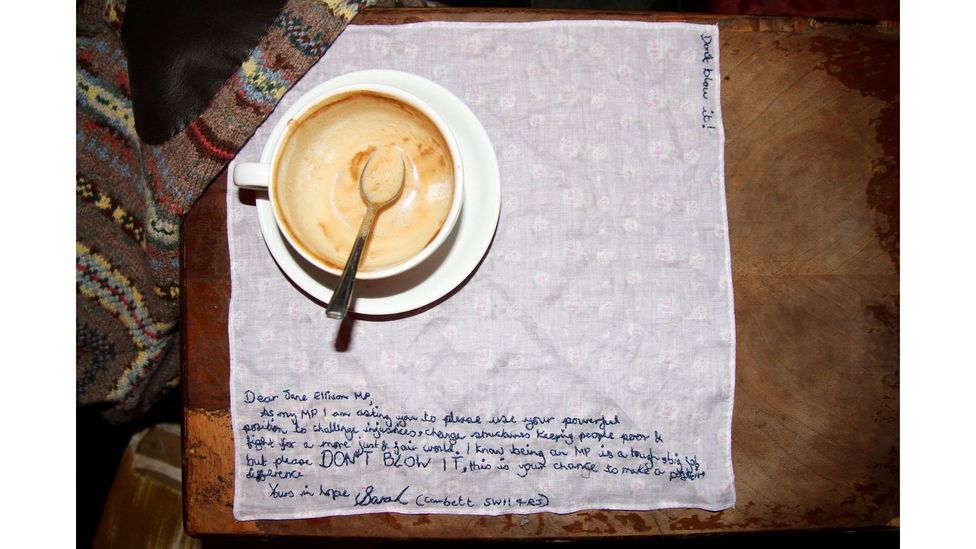

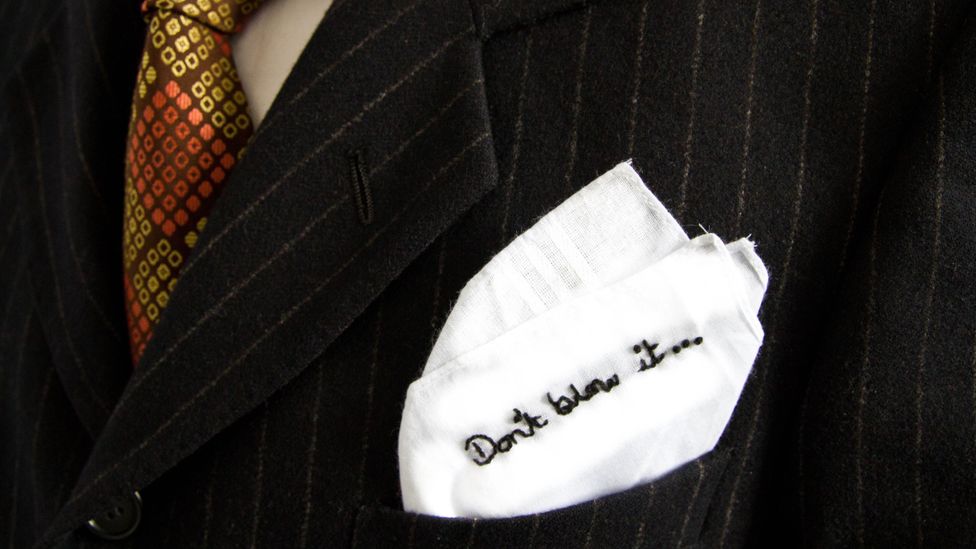

The embroidered handkerchief project aims to give tailored messages to business leaders and politicians (Credit: Craftivist Collective)

While craftivism appears to bridge some divides, in other ways it can be a narrow activity. A lot of groups involved tend to be white and privileged, Corbett acknowledges.

"I grew up in a very low-income working-class area in Liverpool and saw first-hand the impact of inequality," says Corbett. "So I'm very aware that craft can be expensive, you need time and energy to do it and if you're living on the breadline and doing three jobs to support your family, you can't always do it."

Some craftivist projects have been criticised for failing to be inclusive, such as 2017's Pussyhat Project. "If you look at the pussy hats, they're pink," says Corbett. "For people who don't have a pink pussy [vulva], that's an issue."

In the Global North "it is mostly a white activity and it doesn't involve a lot of diverse folks," says Sanders-Bustle. "One could ask the question, why is that?"

But she also points back to where craftivism meets socially engaged art, a field that has been led by indigenous communities and people of colour. In the US, the Harlem-born artist Faith Ringgold's story-quilts have been internationally celebrated. In South Africa, the artist collective the Keiskamma Art Project has embroidered a monumental tapestry that speaks to local experiences of climate change, HIV/Aids, and racial and gender equality.

Carbon Count

Emissions from reporter's travel for this story were an estimated 9kg CO2. Digital emissions from this story are an estimated 1.2g to 3.6g CO2 per page view. Find out more about how we calculated this figure here.

"That whole practice of collective resistance comes out of the Global South in many ways," says Sanders-Bustle. "But in the Global North it's easy to think, 'Oh, we came up with that.' Well, guess what? Maybe we didn't."

While the terms "craftivism" and "gentle protest" may be new, they have long histories. Sanders-Bustle points to the Abolitionists who stitched anti-slavery messages into quilts, and more recently the AIDS memorial quilt, which carries the name of 94,000 people who died from the disease. "I would imagine that these kinds of things have been going on forever," Sanders-Bustle says.

Today's interest in craftivism is just one more stitch in the tapestry.

--

If you liked this story, sign up for The Essential List newsletter – a handpicked selection of features, videos and can't-miss news delivered to your inbox every Friday.

Join one million Future fans by liking us on Facebook, or follow us on Twitter or Instagram.