"Vamos de punches punches punches", Yamilet Muñoz texted her friends in Austin, Texas. It means "let's go and party", but it's not a phrase you'll find in any dictionary. It's a remix of Spanish and English words seasoned with a in-joke about punching the air as you dance, and it's just one example of the countless linguistic innovations happening every day as these two major American languages meet.

"Our language has always been a very big indicator of our cultural pride," says Muñoz, whose parents migrated from Mexico to San Antonio, Texas, in the 1990s. Around 66% of the city's population identify as Hispanic or Latino/Latina (Latinx is also used to refer to Latinos and Hispanics in a gender-neutral way). For Muñoz and her friends there is pride in speaking Spanish, but also in mixing the languages into the hybrid known as Spanglish: "It's like a rite of passage – we are making what we heard growing up into our own thing. It's very natural to use."

It is also, she says, about "integrating the two cultures", as she seamlessly moves between Spanish and English in her private life as well as her job as an outreach associate for the Catholic Diocese of Austin.

The evolution of Spanglish has been documented for decades, with each generation adding its unique twist. Now a growing body of research, as well as the experiences of bilingual speakers like Muñoz, shows just how deeply English and Spanish are influencing each other in the United States – resulting in hybrid dialects like Spanglish, but also, transforming the underlying languages.

"The two languages are shaping one another in both directions," says Phillip Carter, a professor of linguistics and English at Florida International University's Cuban Research Institute. "English very clearly affects the way people speak Spanish here, but Spanish also affects the way that people speak English. The most obvious [result] is the phenomenon sometimes called Spanglish, where people use both languages within an utterance, or both languages within a conversation," he adds.

In fact, according to Pew Research, Spanglish is widespread, with 63% of people who identify as US Latino speaking it at least sometimes. But Carter has also found another effect: Spanish is changing English.

For the past decade, Carter and his colleagues have studied language change in Miami, a city where some 72% identify as Latino or Hispanic and which is strongly shaped by historical migration from Cuba. Their research documents the emergence of a distinct "Miami English" dialect as a result of that Spanish-language heritage.

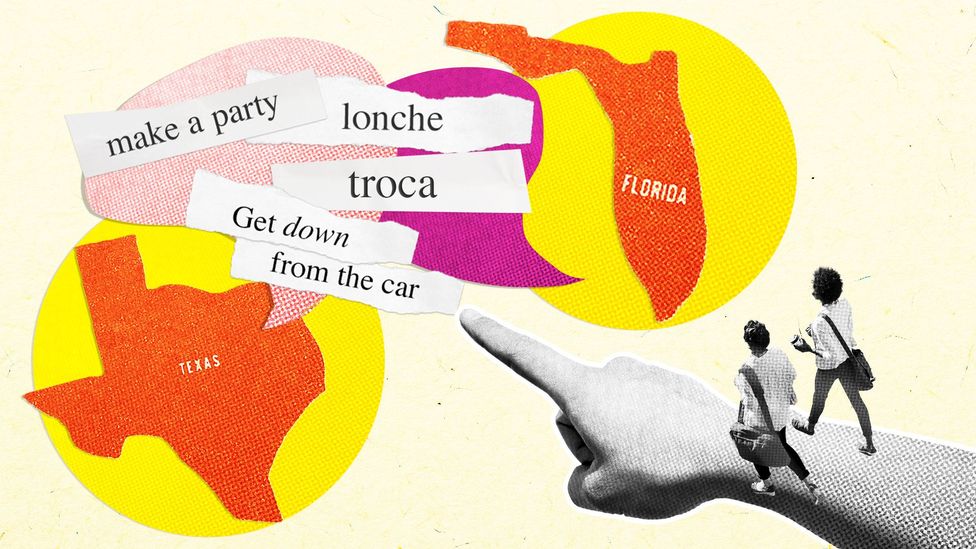

One 2023 research paper by Carter and Kristen D'Alessandro Merii, a doctoral student in linguistics at the University at Buffalo, focuses on the role of so-called calques in Miami English, meaning, English phrases that are translated word-for-word from Spanish. This includes Miami English phrases such as "get down from the car" instead of "get out of the car" (derived from the Spanish "bajarse del carro") or "make a party" instead of "throw a party" (derived from the Spanish "hacer una fiesta").

The Spanish influence has also shown up in ways people may not immediately notice, such as sounds like the "oo" in "boot" being pronounced in a more Spanish-style way in Miami, more like the Spanish "u" vowel, according to separate research by Carter, Lydda López Valdez at the University of Miami and Nandi Sims at Ohio State University.

"This is the work of language change, this is the work of dialect formation, this is how it happens. It happens in things that are really noticeable, like [the phrase] 'get down from the car', but it also happens in really subtle ways," he says.

People wave Cuban flags in the streets of Little Havana in Miami (Credit: Getty Images)

Let's Talk

Let's Talk is a language series across BBC.com, exploring the ancient roots of alphabets, jargon-busting the modern boardroom, and seeking to understand why we speak the way we do. Browse the whole series here.

Meghann Peace, an associate professor of Spanish at St Mary's University in San Antonio, Texas, defines Spanglish as "a dialect of Spanish that is influenced by English". Peace teaches a Spanglish class during which her students also research the dialect. Broadly speaking, Spanglish includes not only mixing the languages but also wider borrowings and influences, she says. She gives examples of commonly used Spanish-English words in San Antonio, such as "lonche" for lunch (instead of the standard Spanish "almuerzo") and "troca" for truck (instead of "camioneta").

Peace also says certain word-for-word translations from English are commonly used in Texan Spanish, such as "correr para presidente" for "run for president" (instead of the standard Spanish "presentarse como candidato a la presidencia", which would translate word for word into something like "presenting yourself as a candidate for the presidency").

Many of the students in her Spanglish class are themselves bilingual and use Spanglish in their daily lives, Peace says, and yet there is a common view among them that "Spanglish is fun, it's cool – and it's incorrect". But, she adds, "it's not incorrect at all". Instead, Peace describes it as simply the result of contact between English and Spanish.

It's not just Spanish and English shaping each other, however. Different kinds of Spanish – from different parts of Latin America and Spain, and different generations – are also meeting in the US and creating something new.

Horse riders carry American and Mexican flags during the Annual Houston Fiestas Patrias Parade in Houston (Credit: Getty Images)

Eloy Cruz, a 22-year-old former student of Peace's, describes Spanish as his first language and one he naturally prefers, though he is also fully comfortable in English. He is of Mexican descent and grew up in the city of Laredo by the US-Mexican border, where more than 95% of the population identify as Hispanic or Latino, and more than 88% speak a language other than English at home. His parents were also born in the US in Laredo, Texas, but lived in Mexico for the majority of their formative years. The family spoke only Spanish at home.

In his work at a public school in Texas, supporting young people as they go to university, Cruz effortlessly shifts between his languages. Many of the students' parents, for example, come from different parts of Latin America, and many only speak Spanish. On the other hand, there are those who may want to learn more English, and then he responds accordingly: "If they start throwing in more English, I'll also throw in more English, to help them out. I need to get a feeling for what they're like, and then I'll throw in more Spanish or English."

He also enjoys trading words from different Spanish dialects: he learned "pana", a Peruvian word for friend, from Peruvian students at his university. He in turn taught them the Mexican expression "nombre", a contraction of "no, hombre!", meaning something like, "no way, man!" Once, he found himself exclaiming: "Nombre, pana!" – "No way, man!", with a Mexican-Peruvian twist.

One of his current favourite words is "eslei", Spanglish for "slay" – as in, to do something extremely well.

New York City's Mexican-American community celebrates Mexico's Independence at the annual Mexico Day Parade (Credit: Getty Images)

Why do bilingual speakers mix languages in this way? One might think it is simply an unconscious, accidental process, but research suggests it is more intentional than that.

Peace has analysed how Mexican Americans subtly change their Spanish when studying abroad in Spain. Research by her and others has shown that during such extended stays in Spain, Mexican Americans and other US Spanish speakers tend to pick up certain aspects of European Spanish, but not others. For example, they often adopt one particular European Spanish word with special enthusiasm, according to the research: "vale", meaning, "right", or "ok".

"They love saying vale," Peace says, even though equivalent words exist in their own US Spanish, such as "bueno".

What made the students adopt this word, but not others? The answer has to do with finely calibrated judgments around identity, research by Peace and others suggests. Sprinkling in "vale" allowed the speakers to add some global flavour to their speech, while still holding on to their own identity, Peace says: "It's seen as cosmopolitan, and shows that you're capable of adapting. It's a way of saying, 'I am an international person'," she says.

Spanglish is helping conversations happen – Yamilet Muñoz

Muñoz and Cruz also highlight another important reason for mixing and shifting between Spanish and English: making sure everyone can understand each other and feels welcome.

"The way we use Spanglish is fluid," says Muñoz. "I could be speaking Spanish, and they'd be speaking English back to me, and that's ok. With those who also speak that way, there's no shame." For her, it also reflects the linguistic diversity that shaped her upbringing in San Antonio. "Growing up, there were so many different types of Spanish," she says. That mix included people newly arriving from different Mexican regions or other Latin American countries, as well as those born in the US, like herself. For her, Spanglish is a way of connecting everyone in that community: "It's what's helping conversations happen."

Some expressions, she says, are also just satisfying to say, such as "no manches!", which she translates as "dang!", as in: "No manches, I forgot my pencil case!"

She can also switch to standard English whenever she wishes, for example during her interview – as well as combining English and Spanish, an ability known as code-switching, meaning, mixing one's languages to adjust to a given context. Research suggests that bilingual children can already code-switch at a young age.

The bigger story is, Spanish is an American language. Spanish has always, always, always been here – Phillip Carter

Carter, the researcher who studies language change in Miami, points out that this is not the first time English has been profoundly transformed by bilingualism. After the Norman conquest of England in 1066, French entered Old English through loanwords. The mix, and other linguistic influences such as Latin, helped create the English we speak today.

"When you have bilingual situations like this, the minds and mouths of bilinguals do shape the language, and it often has effects that are long-lasting," Carter says.

Regarding English and Spanish in North America, that evolution also has a long history, he notes: "English and Spanish have been doing a dance with one another in the United States since the colonial period," he says. "The bigger story is, Spanish is an American language. It's a language of the US, even though it's not constructed that way in political terms. Spanish has always, always, always been here. And although the language itself sometimes gets lost [as families switch to using English], it has influenced the way people speak English."

A woman holds a Venezuelan flag in Miami (Credit: Getty Images)

Despite that long history and profound impact, speaking US Spanish can still trigger negative reactions, whether from Spanish speakers who take issue with the English influence, or English speakers with racist attitudes. According to a survey by the Pew Research Center, four in 10 Latinos report having experienced discrimination such as being criticised for speaking Spanish or being told to go back to their home country – although, more encouragingly, the same proportion had also experienced support. Peace also points out historical discrimination against Spanish speakers in the US on an institutional level, such as punishing children for speaking Spanish in schools.

"Most of the student population here at my university is Hispanic/Latino, which means that most of them speak Spanish. It's kind of comforting knowing there are some people who will understand me if I speak either language or blend both," says Mariana Mata, a 22-year-old student in global studies and Spanish at St Mary's University. Her parents came to the US from Mexico in the 1990s, and she says her mother tongue and main home language is Spanish – though she and her brother use English and Spanish to converse between themselves, and with others. "Although there is so much hate and criticism towards Spanglish, it is one of my favourites because it shows people how our minds work differently," she says.

Elaborating on some the criticism, she mentions a derogatory term used by some Latinos for other Latinos who don't speak Spanish fluently. There has been a rising movement among young bilingual speakers to reclaim the term, including on TikTok, and push back against the implication that some ways of speaking Spanish are inferior to others. "It's a very offensive word," says Muñoz, who is also familiar with the term, and dislikes it. She points out that firstly, it's not a person's fault if they were not taught to speak Spanish; and secondly, US-born Latinos and Latinas may simply speak Spanish differently from their ancestors.

"This is a new Spanish. This is not the Spanish you grew up with. It's not that I don't speak it well. I just don't speak it like you," says Muñoz, addressing those who might take issue with her way of speaking it.

Among his students and their families, Cruz has also observed the opposite pressure: of families losing their Spanish as quickly as possible, to try and protect children from discrimination.

"If you have a good socio-economic status, you're not looked down on for speaking the language," he says, but the picture can look very different for more vulnerable families. In one case, one of his students had been awarded a full college scholarship, but the student's mother did not understand this, and thought they would have to take out a loan. It turned out the student only spoke English, and his mother only spoke Spanish. Cruz, speaking Spanish to her, explained the good news, but also asked her how she and her son had got to the point of not sharing a language. He says she told him: "I thought I was protecting my son by not giving him anything that people around him can use to bully him."

In his view, one thing we can all learn from Spanglish is to be more open to different ways of speaking, and to remember the ultimate goal is communication, not judgment. "There isn't one way to speak Spanish," Cruz notes. "Hey, Spanish might include some English – it might include some Portuguese, depending on where you are. There should be more acceptance of how people speak their Spanish, because at the end of the day, it is theirs."

--

If you liked this story, sign up for The Essential List newsletter – a handpicked selection of features, videos and can't-miss news delivered to your inbox every Friday.

Join one million Future fans by liking us on Facebook, or follow us on Twitter or Instagram.