In October 1687, a dugout canoe arrived at the shores of St Augustine, then a settlement in Spanish Florida and now the oldest continuously occupied city in the mainland US. The canoe carried eight men and two women, one of whom was holding a toddler in her arms. The travellers were Black fugitives who had escaped enslavement by British plantation owners in the Carolinas to the north. After disembarking from their vessel, they headed to the town centre in search of freedom.

"They went to present themselves to the governor of St Augustine," said Jane Landers, a professor of history at Vanderbilt University and a director of Slave Societies Digital Archive, which documents the history of enslaved Africans and their descendants. "They explained that they are asking for his protection, and that they wanted to become Catholics."

The group of travellers had heard that this Spanish settlement was set to become a religious sanctuary and would offer freedom to any previously enslaved person willing to convert to Catholicism. Soon, other enslaved Black people from Georgia and the Carolinas in British Colonies up north began to escape south to St Augustine.

The journey toward freedom could take a week or more and was perilous. The escapees navigated swamps and coastal waters that were full of dangers. In the wilderness, alligators, panthers and poisonous snakes awaited. In towns and villages, slave catchers prowled the streets. The sun was relentless, as were the mosquitos, and it was often difficult to find food and water. Still, for many, the promise of freedom was worth the risk. Sometimes, the local Yamassee Native Americans who lived in Georgia and the Carolinas even helped the fugitives, essentially creating an early Underground Railroad that ran south instead of north.

As early as 1687, formerly enslaved Black people headed south through swamps in search of freedom instead of north (Credit: Linda Burek/Alamy)

These original 10 canoe-bound travellers were the first documented religious asylum-seekers to St Augustine, and unbeknownst to them at the time, they laid the foundation for a more just and egalitarian society. For the next 76 years that followed, a small community of formerly enslaved African Americans lived as free people in St Augustine, transforming it into a town that was dramatically different than anywhere else in the American South.

Unlike the system of race-based chattel slavery employed in the British Colonies, Spain viewed the institution of slavery differently. It followed the old Roman law, in which anyone – regardless of skin colour – could be enslaved if they had been condemned or captured in wars. Yet, under this Castilian code, enslaved people had certain rights and protections, such as the right to be treated humanely and the right to become free either by military service or by converting to Catholicism. Spanish slave owners were also not allowed to break apart families or sell children away from their parents.

Rediscovering America

Rediscovering America is a BBC Travel series that tells the inspiring stories of forgotten, overlooked or misunderstood aspects of the US, flipping the script on familiar history, cultures and communities.

"It's not about skin colour and it's not about race," Landers explained. "Under the Roman law, you have rights. You could report bad owners who were mistreating you, and you could ask for a change of owner." In addition to religion, politics played a role in Spain's differing view of bondage, too, as the Spanish needed more people to defend their territory against the British, who kept attacking their settlements from the north.

St Augustine's governor listened to the 10 asylum seekers and allowed them to stay. As more formerly enslaved Black people kept coming in the following years, the king of Spain issued a proclamation in 1693. "If anybody runs away from a Protestant colony and comes to a Catholic colony requesting the 'true faith', as they called it, you must receive them and protect them," said Landers, who studied the archival records in Spain for her dissertation. "For the British, everything was about race and skin colour. The Spanish were, 'are you a Catholic or not?'."

St Augustine is the oldest oldest continuously occupied city in the mainland US, but in the 1690s, it was a small frontier town (Credit: Allen Creative/Steve Allen/Alamy)

In 1693, St Augustine was a small frontier town frequently raided by pirates and the British. Around the time these early freedom-seekers escaped to the settlement, the government decided it wanted to have a northern outpost to monitor their British neighbours and alert residents in case they had to seek shelter. So, in March 1738, Governor Manuel Joaquín de Montiano built an outpost just north of St Augustine called Garcia Real de Santa Theresa de Mose (pronounced "Mo-say").

Tour St Augustine's Black past

In addition to visiting the Fort Mose Museum, the Lincolnville Museum and Cultural Center and the Lincolnville neighbourhood, visitors should also look for 31 historic markers along the Accord Freedom Trail identifying various sites significant to the Civil Rights movement that took place in St Augustine.

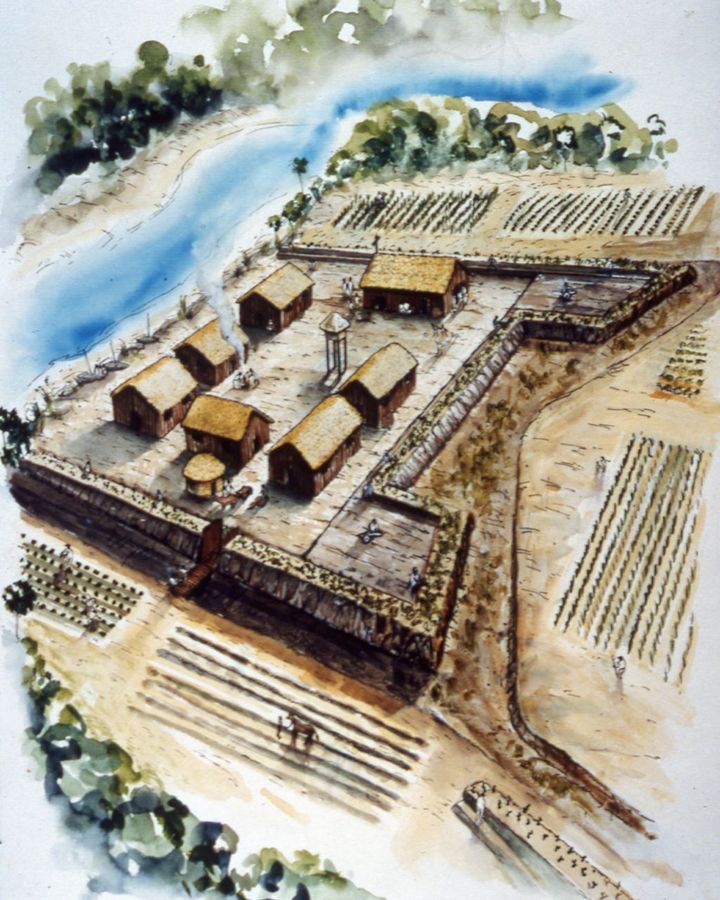

At the time, approximately 100 free Black people were living in St Augustine, and enjoyed equal rights as their European neighbours. They helped the Spanish build the few thatched huts surrounded by earthen walls that would become Fort Mose. The fort housed 38 men and their families, the majority of whom were Black. The men served in the Fort Mose militia scouting the surrounding area – some on horses, some in canoes, others on foot. Although a Spanish officer was nominally in charge of the fort, a Black man named Francisco Menéndez, who had escaped from a South Carolina plantation, was its de-facto captain and military leader.

Today, the fort and town of Fort Mose is considered the first legally sanctioned free Black settlement in what would later become the United States. An interactive museum now highlights the fort's history and displays artefacts discovered during the site's excavation.

Two years after Fort Mose's construction, British troops attacked and seized the fort, eventually destroying it. But just 16 days later, members of the Black-led Fort Mose militia and Yamasee warriors banded together in an early morning surprise attack to defeat the British in what's now known as the Battle of Bloody Mose. These Black and Native soldiers felt compelled to defend their territory, but also their human rights, which they knew would be better protected under Spanish rule than British. While Fort Mose was in ruins, its former Black residents moved back into St Augustine where they intermarried and integrated into society.

Fort Mose was the first legally sanctioned free Black settlement in what would become the US (Credit: FloridasHistoricCoast.com)

"It was a very diverse community, culturally and ethnically, in all kinds of ways," said Regina Gayle Phillips, executive director of the Lincolnville Museum and Cultural Center, located in St Augustine. Housed in the area's first public Black high school, the museum's exhibits stretch 450 years, from the empires of West Africa to the early Black presence in colonial Florida to today.

In 1752, Fort Mose was rebuilt in a slightly different location and the Spanish government once again asked some of St Augustine's Black residents to guard the outpost. When they weren't keeping an eye on the British, residents also farmed, hunted, fished and had the same rights as whites. But 11 years later, in 1763, the Spanish traded Florida to the British in a peace treaty, effectively extinguishing this small island of freedom in what would become the US South.

"Everybody had to pack up and leave because they knew the English were going to come and establish that same harsh kind of slavery, where they are considered nothing more than a piece of property," said Landers. And pack and leave they did, moving all the way to Cuba, which was kept under Spanish rule in the treaty.

"Everyone in St Augustine left, even the Native American people," said Kathleen Deagan, an archaeologist and adjunct professor of anthropology and history at the University of Florida who has spent nearly half a century unearthing St Augustine's past. "We get the sense from the documents that what they really didn't want to do was live under Protestant rule… but certainly they didn't want to live with the British, their former enslavers." As a result, Fort Mose fell into disrepair and was soon abandoned and forgotten.

Lincolnville, where Black people formed a free community, is now listed on the National Register of Historic Places (Credit: State Archives of Florida/Florida Memory/Alamy)

When slavery ended after the end of the US Civil War in 1865, Black people who had been brought to St Augustine under British rule formed a free community. Initially called Little Africa, it was soon renamed Lincolnville, after the assassinated president, Abraham Lincoln. The free men and women leased land along the marshy banks of the Maria Sanchez Creek, making it their home.

"[There] used to be orange groves, which were divided up and leased to people starting at $1 per year," Phillips said. "Some of the families' descendants still live here." Lincolnville was listed on the National Register of Historic Places in 1991 and today, the 45-block neighbourhood is home to many Victorian homes and businesses dating from its founding by freed Black people.

St Augustine and its residents also played a pivotal role in Black liberation in the Civil Rights movement. In 1964, the city's civil rights leader Robert B Hayling invited Martin Luther King Jr to join forces with local protestors. On 9 June 1964, King was arrested after refusing to leave a segregated restaurant at one of the city's motels, which made national news. Later, his aide, Andrew Young, led a night march from Lincolnville to St Augustine's Constitution Plaza (the oldest public space in the US) where they were attacked by an angry mob, which also was widely covered in the media. A bronze sculpture at the eastern end of the plaza proudly displays the faces of those who peacefully protested during the Civil Rights movement in St Augustine, while on the western end, visitors can retrace Young's Civil Rights march by following the brass footsteps on the pavement.

Just a few days later, the motel's manager was photographed pouring acid into a pool where both Black and white people were swimming together to protest segregation. The incident spurred protests that went on for days. It was broadcast on TV and printed on the front pages of newspapers across the world. Finally, on 2 July, President Lyndon Johnson signed the Civil Rights Act into law, which prohibited discrimination on the basis of race, colour, religion, sex or national origin and ushered in integration of schools and other public places.

A monument in Constitution Plaza commemorates the many peaceful protestors who helped propel the Civil Rights movement (Credit: Allen Creative/Steve Allen/Alamy Stock Photo)

"St Augustine's events were pivotal [to the passing of the bill]," Phillips said.

Today, the historic Fort Mose has been reconstructed at its second location. Visitors can see renderings of the original fort at the Fort Mose Museum, and also trace the story of the first legally sanctioned free African settlement in the museum's interactive exhibits. Throughout February for Black History Month, and in June (the month when the British attacked the fort), local actors recreate the Battle of Bloody Mose. The Lincolnville Museum and Cultural Center also has exhibitions about the community's origins and St Augustine's Civil Rights era. With hundreds of artefacts and photos, it highlights the stories of local Lincolnville residents and protestors, including a police fingerprint card documenting Martin Luther King's arrest.

As Phillips said, "We're just trying to make sure that people understand the richness of the history that started here over 450 years ago."

Rediscovering America is a BBC Travel series that tells the inspiring stories of forgotten, overlooked or misunderstood aspects of the US, flipping the script on familiar history, cultures and communities.

---

Join more than three million BBC Travel fans by liking us on Facebook, or follow us on Twitter and Instagram.

If you liked this story, sign up for the weekly bbc.com features newsletter called "The Essential List". A handpicked selection of stories from BBC Future, Culture, Worklife and Travel, delivered to your inbox every Friday.