Light rain was falling as I drove through the foothills of the aptly named Montagne Noire (Black Mountain), a mountain range in the southern French Occitanie region characterised by dark forests of oak and pine. As the rain softened to mist, a rainbow appeared, illuminating Montolieu's medieval Saint-André church. It seemed like a promise that something magical awaited. And for a bibliophile like me, it did.

Montolieu (population: 833), is home to no fewer than 15 independently owned second-hand bookshops, making it southern France's only official Village du Livre (Book Village).

Montolieu isn't the only book town in the world. Wales' Hay-on-Wye, home to more than 20 bookshops, was first recognised for its bibliophilia in 1963; Belgium's Redu, which once counted 26, earned the status in 1984. Montolieu isn't even the only book town in France; Brittany's Bécherel became the country's first in 1989 and has since been joined by seven more, including Montolieu in 1990. But France's second-oldest official book town stands out for a simple reason: unlike its sister villages, Montolieu's focus was never meant to be on the sale of books, but rather on their creation.

Bookbinder Michel Braibant first dreamed up this booktopia in the 1980s: a village that would double as a conservatory for bookmaking arts.

For the past 35 years, Montolieu has been synonymous with books (Credit: Alamy)

"It was [a] completely off-the-wall [idea]," said Gaëlle Ferradini, the new director of Montolieu's Musée des Arts & Métiers du Livre, a museum devoted to the art and craft of bookmaking. That it worked, she says, is a credit to Braibant himself. "People tell me that he was the kind of person you went along with, in his projects."

Today, the museum is home not only to exhibits on writing systems and machines like a Heidelberg printing press but also to regular three-hour workshops, taught by 12 visiting Southern French artisans who come to share their mastery of marbling paper, engraving or Latin calligraphy. Bookbinding is taught by Camille Grin, perhaps Braibant's most direct successor. An artisan-in-residence, Grin operates her workshop out of the museum's second floor, taking full advantage of the antique machines, many of which came from Braibant's personal collection, to exercise her craft.

"I tell myself he'd be happy to know that in this museum – which was never really meant to be an aesthetic museum, but really a living space – there's an artisan, working," she said.

Montolieu's unique status helps it stand out from its neighbours in this sleepy corner of France near the Pyrenees. While the tourist season officially opens with a massive Easter weekend book market, and summer sees the 18th-Century textile factory at the bottom of the village transformed into a cultural centre that hosts concerts and art exhibits, even on a February Friday, the village streets were filled with life. People sipped pints in the brisk sunshine outside the cafe or lunched at one of six restaurants flourishing along the cobbled medieval streets. They dipped in and out of artisan boutiques, as painters, fashion designers and even a potter have set up shop in the village's many half-timbered buildings. And while there are no ATMs in Montolieu, you can purchase groceries with the push of a button: two local farms fill refrigerated vending machines with organic produce daily, including some of the sweetest, juiciest apples I've ever tried.

Montolieu is a tiny village filled with artisan boutiques, restaurants and – of course – books (Credit: Alamy)

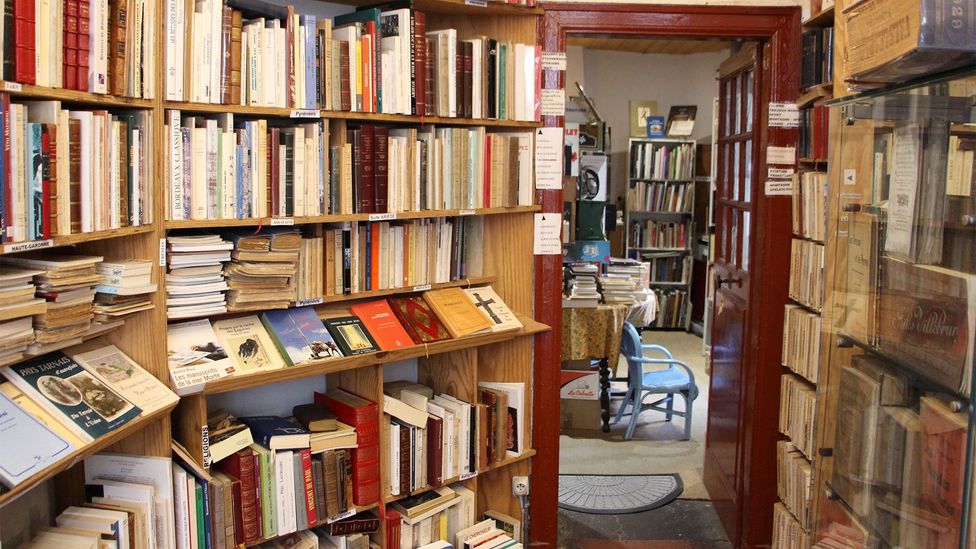

And of course, people shopped for books. Montolieu's bookshops may not have been the original focus of Braibant's dream, but they certainly draw tourists today. In the early 1990s, Braibant and other members of the association he had founded reached out to booksellers, tempting them with the promise of picturesque storefronts, which then lay mainly empty following years of rural exodus. Concentrated chiefly around the rue de la Mairie, they boast creative signage, often offering a hint as to the bookseller's specialty. L'Art et la Manière focuses on art books; the shelves at Mamézon are chock-a-block with comics and manga. Contes et Gribouilles' colourful storefront evokes its dedication to books for children "from 0 to 99 years old".

I began my discovery at the slightly more exocentric Au Temps de Jadis, with its inviting scent of old paper and shelves crammed with leather-bound tomes. A slightly taciturn shopkeeper introduced himself as Jean, but the moment I asked what he was reading, he thawed, showing off his periodicals and satirical journals, not to mention a 1670 copy of Les Pensées de Pascal, its pages as thin as a butterfly's wings. It turns out Jean-Noël Ortis' specialty is books on philosophy and history, particularly Napoleon III and World War Two. "But of course," he said, "when you like history, one could say you're curious about everything."

One might think that the sheer quantity of bookshops in a village so small would invite competition, but Ortis assured me this is far from the case. On the contrary, he said, most booksellers are happy to send clients to their colleagues in search of a specific tome. "That way, everyone's happy," he said. "It creates harmony among us."

This community-minded outlook was evident as I entered La Rose des Vents' bright pink storefront to find no bookseller, just a tumble of tomes dedicated chiefly to sciences and artisan crafts and a sign saying, "I'm upstairs, I'll be right down!" A few moments later, owner Marie-Hélène Guillaumot appeared as though conjured – which she was, she told me, thanks to a motion detector that switched on the radio in her flat upstairs, where she occupies herself during lulls by carrying out her bookseller's tasks – such as covering books in plastic – as well as "making soup or ironing".

La Rose des Vents is filled with mountains of old books (Credit: Emily Monaco)

Rob Kleiss, my host for the night, also spent more than a decade living above his bookshop, Abélard. His former abode is now home to a plethora of books in various stages of well-loved battery, waiting to be restored or shipped; he lives across the way in a building he purchased in 2017, transforming it into a book-lovers' bed and breakfast. My loft-like room on the second floor was awash with light, illuminating the leather-bound books atop the mantle and on shelves built into nooks and crannies. Antique caricatures decorated the bathroom walls, and from the window, I glimpsed the aptly named Chapters restaurant, still bustling at 21:00. At the other end of the room, a cosy chair was placed before a window revealing the Black Mountain in the distance, the sky awash with starlight.

These views were part of what brought Englishman Adrian Mould to Montolieu. After more than a decade working for the trade union of the tiny local Cabardès wine appellation, known for is unique combination of Mediterranean and Atlantic grapes, Mould opened his wine cellar in 2011. "I have a very regular and loyal local clientele," he said. "Generally, booksellers like wine."

The village is saddled between two rivers, the Dure and the Alzeau, which Mould says, "bring it a lot of energy". Indeed, the power of the water made it a 19th-Century textile centre, and at one point, six paper mills dotted the banks of the Dure. The 300-person village of Brousses-et-Villaret, a 15-minute drive away, is home to the last one still in use in all of Occitanie, and the morning after my stay at Abélard, I drove into the fog-shrouded hills and trekked along the surging river to the mill, where Sabine Durand-Hayes was waiting.

Durand-Hayes is part of the seventh generation of the Chaïla family, which has produced paper and then cardboard here since 1877. When her grandfather retired in 1981, it seemed the family trade would be lost, until Braibant's widow implored Durand-Hayes' uncle, André Durand, to take up the torch, which he did in 1994. Today, Durand-Hayes is responsible for many of the mill's administrative tasks, joking that she works "in paperwork, but not the same kind". She knows her family's ancestral trade well enough to lead enlightening guided tours, which the mill offers in addition to frequent paper-making workshops.

Durand-Hayes is a seventh-generation papermaker who leads demonstrations in the nearby village of Brousses-et-Villaret (Credit: Emily Monaco)

"We don't call ourselves a museum," she said, noting that theirs is a living, working production site. "We're perpetuating a craft here."

The enduring presence of Montolieu's mills are a reminder that this small village has long drawn outsiders, notably thanks to its textile factory, which reached its peak of 257 workers in 1812, producing cloth exported as far as China. The tiny village retains a rather cosmopolitan atmosphere today. "At one point, we had 17 nationalities," Guillaumot said.

The village's openness may have cemented its bookish destiny. After all, Braibant initially proposed the idea of creating a book village in his then-home of Saissac, located 9km away from Montolieu. Yet, Guillaumot told me, "In spite of the esteem that people had for [Braibant], they found [his idea] ridiculous." But here in Montolieu, they were willing to take a risk on what Ferradini termed "a different kind of tourism".

Braibant passed away in 1992, his dream barely realised. But today, his legacy lives on in this little town, a hidden paradise for book lovers, ready to welcome anyone who seeks it.

---

Join more than three million BBC Travel fans by liking us on Facebook, or follow us on Twitter and Instagram.

If you liked this story, sign up for the weekly bbc.com features newsletter called "The Essential List". A handpicked selection of stories from BBC Future, Culture, Worklife and Travel, delivered to your inbox every Friday.